Why should art students learn to draw from life? My students; photography majors, graphic design majors and even illustration and studio majors do not readily understand why learning to draw accurately from life has significance for them. The answer to that question is complex, and I want to explore it more fully, but first, perhaps we should be asking a more important question. What does “learning to draw” really mean.

Most contemporary course descriptions define drawing as the development of technique through experimentation with the materials used in making art. Yes, in part I believe it is useful to study tools, materials and techniques, but I also believe this approach is very shallow. It is too specific and disconnected from both our real-life visual experience and, as a result, the language of art. Let me explain why.

Drawing is about relationship.

Drawing is not about rendering or effects or realism. It is about relationship, just pure relationship. How one mark relates to the next, how they in turn relate to the rectangle of the page and, ultimately, what those marks mean to the artist who created them and the viewer who receives and reads them visually and spatially.

To understand this one needs to look at the history of picture making. I use the words “picture making” to differentiate between the making of a visual image and the “art historical” understanding of art. They are not the same. Modern art education has conflated the two subjects, art and art history. The art of drawing is not explained, as many art historians would like us to think, by a series of historical progressions that somehow lead to a unique, improved, and culturally appropriate product. Rather, it is a very precise skill and a universal language of visual form and space that has been built and refined over time by many thousands of accomplished and talented people. This language was developed out of our need to connect with our visual experience of the world and with each other.

Drawing speaks very specifically to our experience of place as a visual and visceral experience. I believe that if you look and deeply study the formal language embedded in great art, you will experience not only the expression of a particular place and time but also the universal experience of being in a physical world. This universal experience reveals the connecting threads of artistic form from wildly diverse times and cultures. I am referring to the connection, the visual vocabulary of relationship and space, which is the true language of drawing.

The Modern Dilemma

Our modern methods, how we teach drawing in most schools today, tend to rely on outliers. The opposite camps are the realist and the conceptualist, both of which are disconnected from the historical language of drawing. Let’s first talk about what I am going to call the realist group. My suspicion is that the disconnect between great representational works of the past and most modern realist painting began with what we now call “academic training”, the nineteenth century version of the art school. I believe that the reliance on teaching specific techniques as a way of learning to draw or paint as opposed to direct study with a master, (or, by way of substitution, from the work of the masters), has grossly simplified if not entirely omitted much of the subtlety, power, design and formal language achieved by past masters. The products of this narrow technical education were and still are, deeply dissatisfying.

In reaction, an outpouring of beautiful and rebellious modern work of the late 19th and early 20th century was created. For most modern art historians this work is interpreted as a rebellion by the artists of the period directed against the traditional language of the visual arts, when in fact that is very far from the truth. Actually, those artists were attempting to hold onto the spatial formal language, the formal thread of artistic endeavor, and jettison the veneer of realist painting. In our modern academic schools we are still educating painters who create every detail meticulously. The work concentrates mainly on surface and lacks spatial tension, rhythm and unity, and consequently the power found in the great works of the past. It would seem that contemporary realists still don’t see the beauty, power and design they are missing.

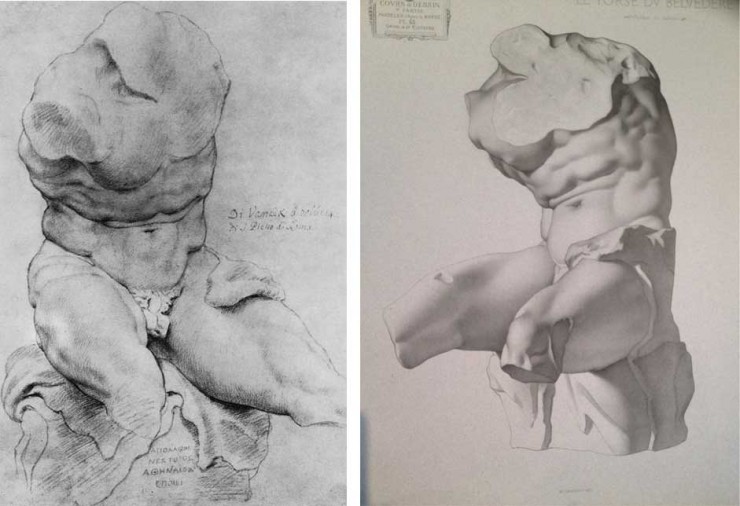

But before we get to the conceptual camp, I think it is worth mentioning here the work of those late 19th and 20th century artists who were in the transitional period between the apprentice system, where the apprentice worked in the masters studio, and the early art-school type systems which we have now. They were basically autodidacts, they spent a great deal of time studying past masters and teaching themselves the language. They reinterpreted it for themselves and in doing so created innovative and personal work based on what they learned. We do have records of some of the studies these artists made and we can see clear re-use of ideas and compositional structures that have been understood digested and re-purposed. I think it is interesting to look at work from some of these artists. What is kept as essential, and what is discarded, can tell us a lot about the language that both connects with visual experience and speaks to different times and cultures. The work was revolutionary in some respects, and deeply traditional in others. After a look at conceptual-ism we will look some of these revolutionary traditionalists.

On the other side we have conceptual-ism the opposite outlier whose directives seem to require complete “originality” to the point of a total disconnect with any shared universal visual language. Now we have discarded not only the superficial veneer of the realist but also severed all connection with the language of seeing. So what is this disconnect? If art is, as many modern art historians interpret it, a linear and progressive activity; then clever concepts or works created whole cloth by individual geniuses with no parameters of artistic language will have no need for criteria that marks a work as successful or unsuccessful. Our only criteria is its supposed individuality and uniqueness. Sadly part of this “uniqueness” is often a complete disregard for beauty, design or form which are simply excluded from the vocabulary. In this play-book it’s all great and it’s all terrible, neither matter.

The popularity of the conceptualist “style” is in part a reflection of our personalization of art; connection and communication become about thumbing ones nose, clever political statements or overwhelming the viewer with unintelligibility. It is art that is definitely not about internal relationships, neither to the visual language of past work, nor to the viewers experience of the world. I suspect part of the attraction of this way of working is the no-fail aspect of its making, the artist need not be vulnerable to failure. The viewer is left confused and in need of explanation, enter the critic and historian to explain what’s what. The verbal explanation replaces visual coherence in the actual work.

I should also add here that I do not believe that all works that grow from the “realist” or “conceptual” realm are without relationship to the language of form, space, design or beauty. However, it has become difficult for those not versed in or sensitive to that language to distinguish between one and the other. More reason to teach the skill of drawing and appreciation of skillful work, not just for students of the visual arts but for everyone.

The Place In-Between

How does the language of art relate to our real life experience? For me the activation of space and form in a work of art re-creates both light and a tactile almost physical sense of form. Tension and ambiguity create movement which in turn mirrors our actual life experience. It is play. Imagination wed with experience and made sensate. If we look to late 19th early 20th Century revolutionary artists we see their broadening connections to past art. And not just in those artists who seem still securely tethered to customary styles, Delacroix comes to mind, but also in artists who seem to transform everything we know about how the world looks, Picasso would be a good example. Carried over is the painterly language of constructing space and tension, which in turn create rhythm and mirror that part of our visual experience. I believe this formal spatial sensibility makes Picasso’s distortions of form seem right and true. It is not just about what he left behind but equally about what he retained. Matisse transformed how we think about color and yet his work maintains a strength of space, form and beautiful design. The transformational work of the moderns is anything but arbitrary and is in fact tightly woven into the historical tradition.

So why should we draw? We should work from nature to develop our understanding of what it means to see. To explore the mysteries of our visual experience. We need to confront the problems that arise when we try to recreate a communicable visual world, for in these problems lie the birth and meaning of our visual artistic language. And we should copy the Masters to experience the solutions to these problems great artists have invented. We can then understand visual language first hand, and in the process explore the underlying principles of great art.

Here are some links to sites that explore copies made by past masters and the interconnectivity of great art.

Hi. My name is Brelynn. I m 13 years old, I m going to be 14 on June h. I ve tried everything to drawing turtorials to chibi. I really like to draw and I figure I want to be a artist someday.. I don t know what to draw or how to do it. I really want to be able to draw the easiest kind of drawing though. What do you think I should do? What would you suggest I try for a good, easier kind of drawing that looks cool. Maybe still life? I just.. I don t know why I can t draw good.. I have a sketch book and stuff. I don t know what to do. Hopefully you reply back soon. I hope I can at least begin to draw good ??