“Raphael and Visual Intelligence”

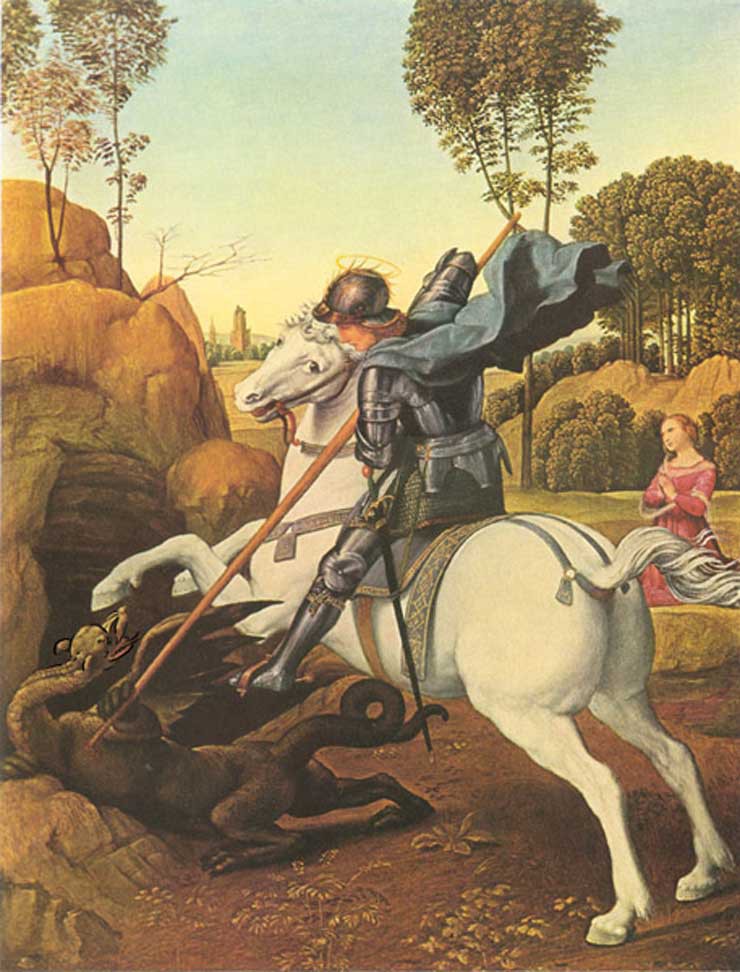

St.George and the Dragon by Raphael is a really interesting painting, it is surprisingly small, (11 1/8 x 8 3/8 in), I was expecting something much larger the first time I saw it in person. My little study is about one aspect of the painting, St.Georges spear and how it relates to an idea I read about in Donald Hoffman’s book “Visual Intelligence”.

This book explores how we see and the basic rules used to construct our 3D reality. I discovered it one day wondering around the bookstore and have found it useful. It’s by a scientist written for a non-scientist and has given me a lot to think about. I think artists use the rules laid out in the book either consciously or unconsciously. For the artist it’s all about “bending” the rules to fool the viewer into experiencing space, form, and movement.

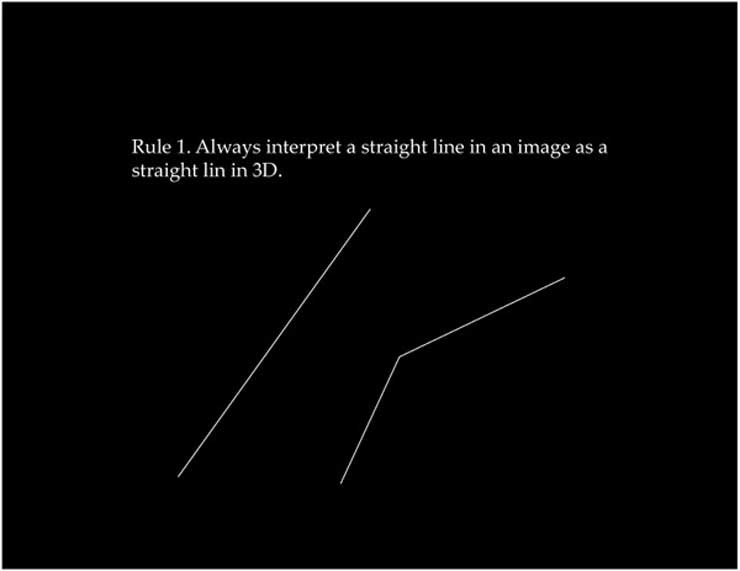

Before we get to the first rule which applies to St. Georges spear, you need the rule of generic views, and it is: Construct only those visual worlds for which the image is stable. So, by default your visually constructing brain will choose the most likely and consistent interpretation of what you are seeing. In this first rule you “could” be seeing a bent line from the only point of view in which it would look straight to you, however if you move your head just a little the illusion of a straight line would be lost. Rule one says that we will read a straight line in a 2D image as a straight line in 3D. Raphael was having some fun with this and using it to open up spaces in his painting.

Raphael’s Geometry and the Strange Spear

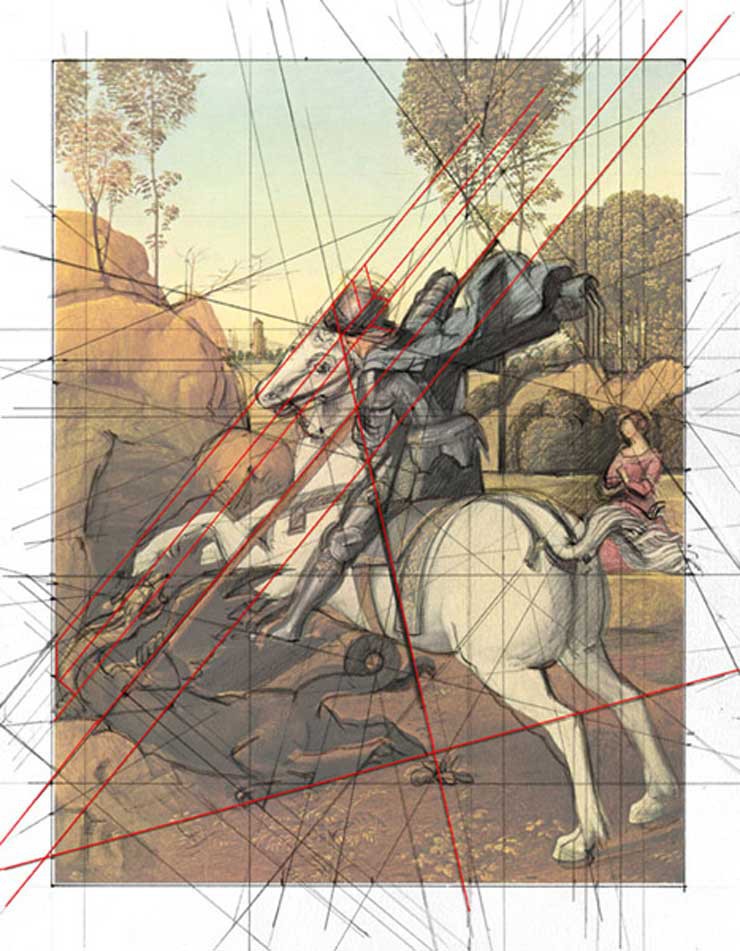

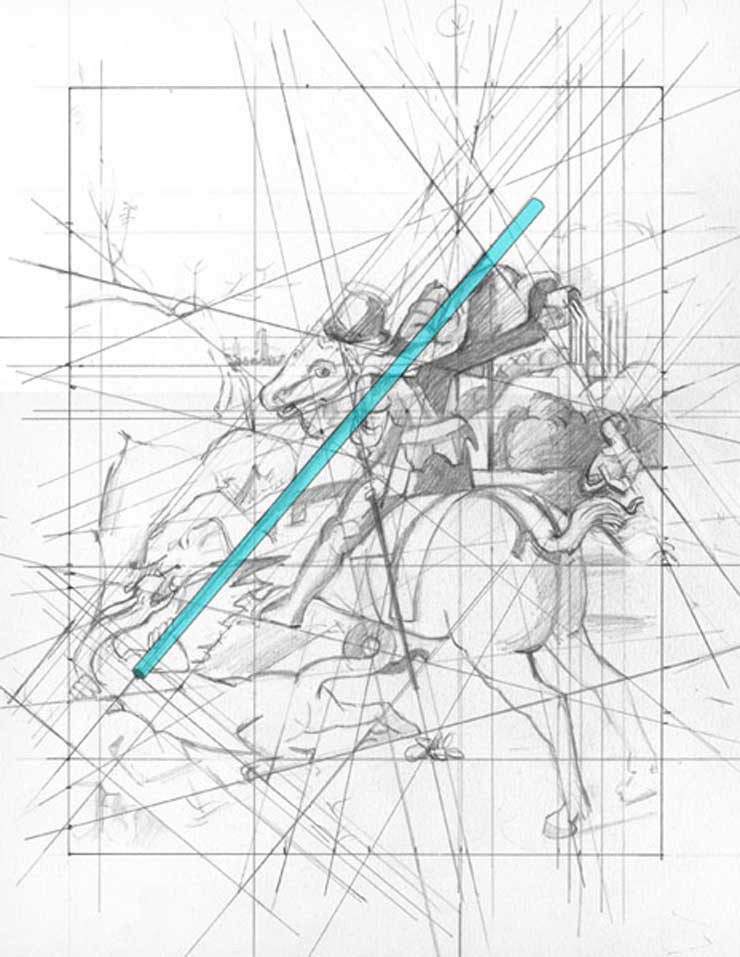

This is a study of the painting with an overlay of my drawing and another made in adobe illustrator (the red lines). You can see how important the angle that follows the spear is to the composition. The two secondary lines are found using the sword and the feet of the dragon. I included them so you could see what a marvel of triangular shapes Raphael created. It’s also interesting that when you repeat the angle of the spear at the edge of the horses face, the helmet front and side you get a very strong connection with the dragon below. I think this is rather like the Boucher with the tension of the story connected to the tension in the geometry. But back to the spear.

This is a study of the painting with an overlay that describes the spear direction. The blue tube takes the place of the spear in the Raphael, I am using it so you can see the tube ends to see logically which part of the spear is closer to you and which part goes back in space. If the spear goes toward us at the bottom, the dragon is deflecting the spear and pushes it away. But take a closer look!

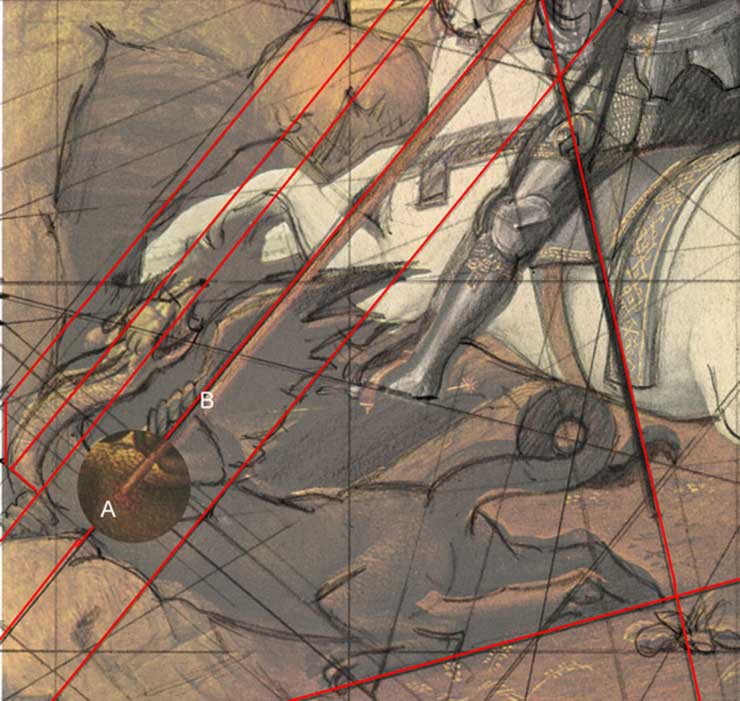

A close up of the end of the spear – which is piercing the dragon, Raphael even gives us a bit of blood around the entry point. If you now go back to #1 you might see the impossible spear that goes back in space behind St George and goes into the dragon below the horses feet.We must see either that the dragon is very much closer to us than the horse or, a very bent spear. The beauty for me is that I see both possibilities depending on how I read the painting. If I am looking close, piece by piece especially in the area of the dragon, then I feel the spear is going into the dragon which is under the horses feet. If I stand back I see the picture as a unity and the spear as one straight line. The next two are representations of possible planes generated by the geometry.

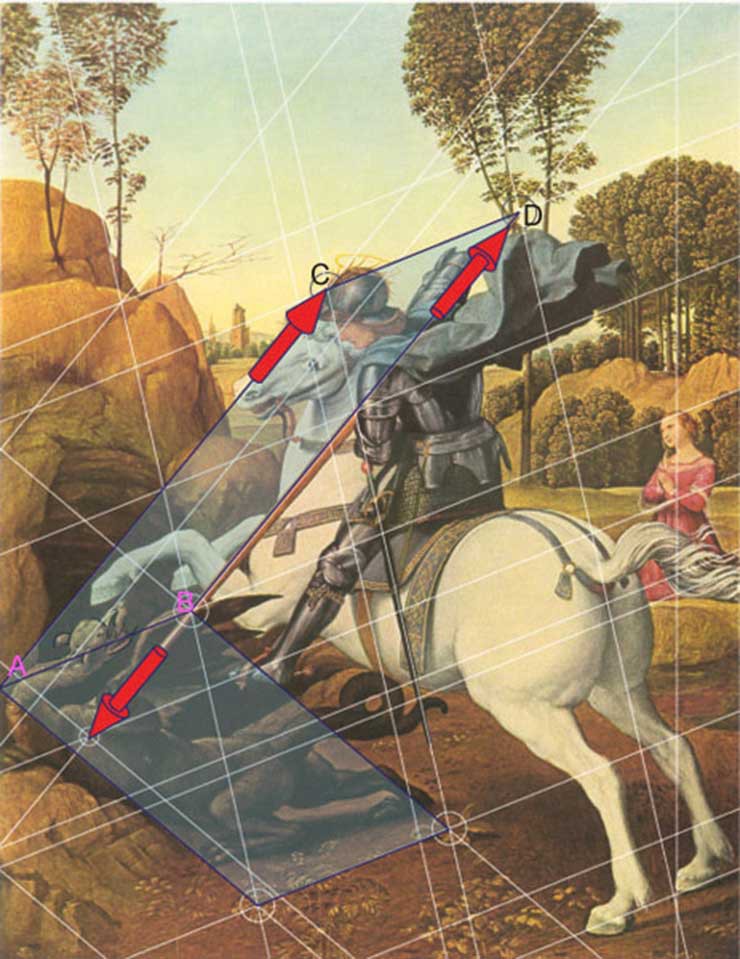

With my husband’s help making these directional arrows I can illustrate some of the possible readings. You can see a little more clearly how the spear would have to bend and how the two blue planes formed by the diagonal structure can be read in different directions. If we look at rotation point B as closer to us than rotation point A, the dragon is pushed forward in space and more space opens between the horse and the dragon (plane A>B>D>C it helps if you cover up the arrow at C).

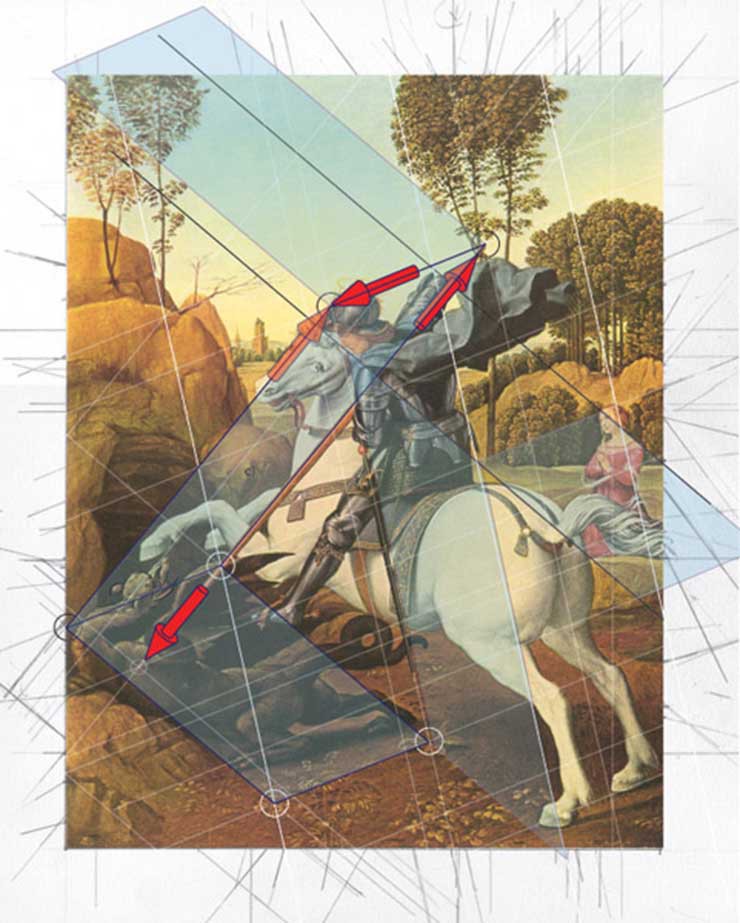

If we see instead A as closer than B, then St. George is pulled forward into space creating more space between him and his horse (plane A>C>D>B cover up the arrow at D). The painting is way more complicated but I find it good to think about an idea pulled out of the whole. It’s confusing enough! The last one is a drawing with a few more added planes.

This is some playing around with possible planes and the triangles that develop between intersections. The painting has more diagonals than are shown here (at least six that I am sure of) and so more possibilities. The plant that is under the horse – one of the white circles (rotation points) marks it, is kind of a mini-reflection of the paintings geometry – pretty funny.

Leave a Reply