What exactly does composition mean for the painter?

I believe it is the organization of elements in a unified manner that guides the viewer on a visual journey. Not so unlike a movie maker edits and selects scenes to create a reality for movie goers. Great painting is not static. As a student I spent a lot of time copying in museums – I wanted to know why my experience of some paintings seemed so much more powerful than others. Why do we say that guy is a great painter? Although each of us has to find the answer for ourselves to this question, the reality is there in the work – and thankfully, available to anyone who chooses to look for it. These pictures are an attempt to relay some of the questions and answers I have found on my journey.

This painting by Boucher was my first museum copy. I learned a few things then and more in the years since. The first involves the Necker cube and ambiguity.

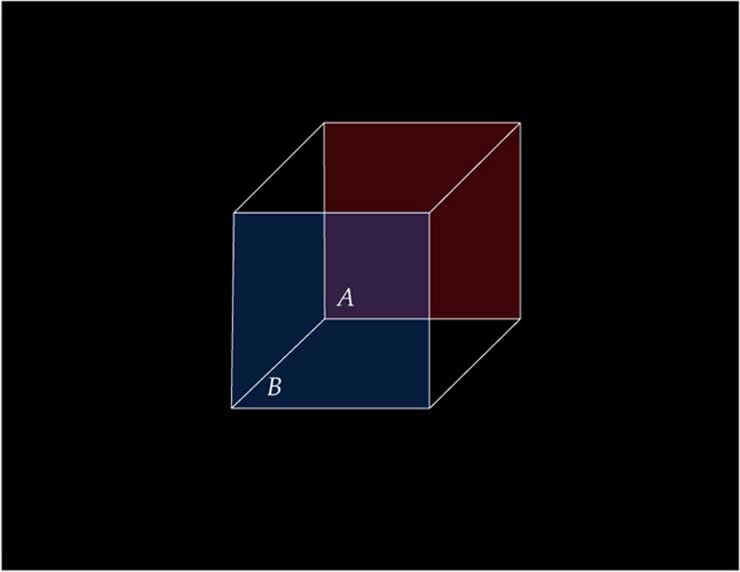

This is a necker cube, the image was first published in 1832 by Swiss scientist Louis Albert Necker. Which plane is in front A (red) or B (blue)? If A is in front, (closer to you) then we are looking at the underside of the cube if B is in front then we see the top plane of our cube. Since your perception of 3D is constructed in your brain you can see both possibilities interchangeably.

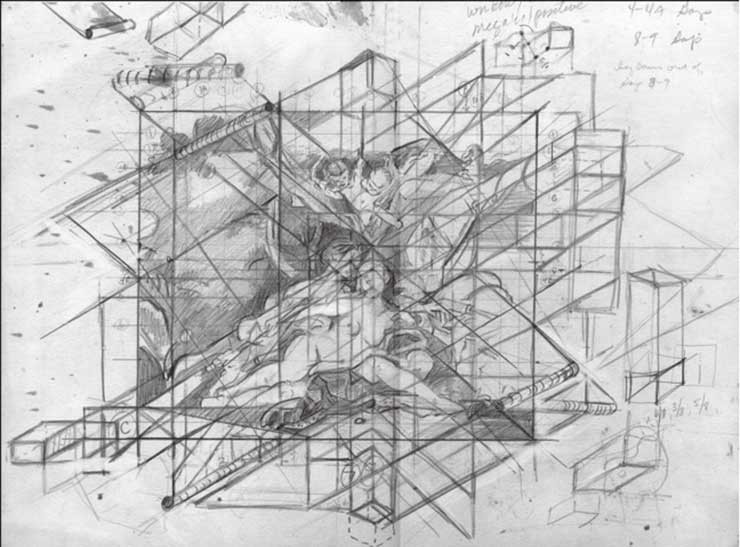

Eventually the Necker cube helped me make sense of the strange experiences I had while copying the Boucher at the museum. My perception of the length of the front figure’s arm kept changing, it would feel right one day and wrong the next. I didn’t solve that mystery at the time but I did start to see that there were strong horizontal and vertical connections in the picture. I explored these ideas some years later working from a B&W reproduction. The drawing, (#3) and the extended Necker cube (#4) tell that story.(-> #3)

This is a drawing that explores some of the interconnections in the painting. You might notice a kind of cube – X composition. The X centers around the heads and the direction of the two figures gaze. You should also see a strong vertical connection with this center and the center and right foreground. There is some pretty complex drapery action going on here and I found that my eye was pulled into this area repeatedly. Sort of like going out to explore other areas of the picture and then home again. I think of the composition like an extended necker cube, Becoming aware of the path my eye follows when I read a painting has been very useful in both my learning and in my own work (-> #4)

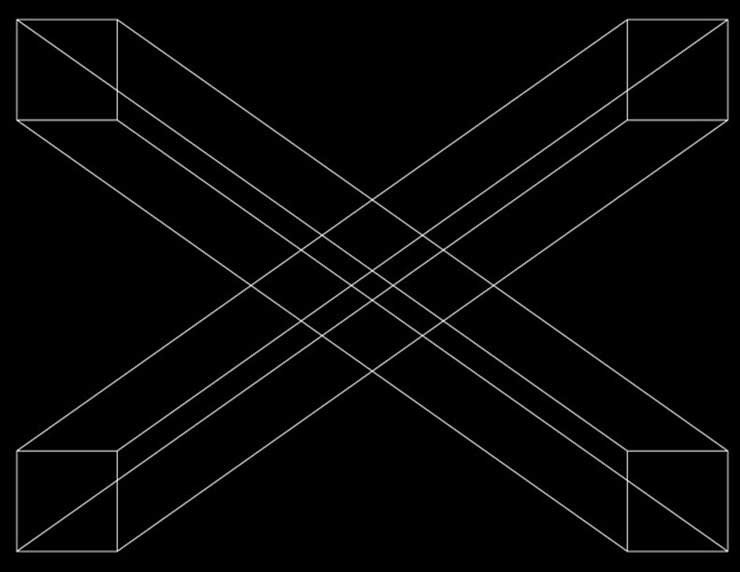

This is an illustration of extended Necker cubes. It is interesting that the two upper corners read as if we are looking up – the square comes forward (red view): and the two bottom corners read as if we are looking down (blue view) even though neither view is stressed in this simple drawing. You can see this reversed but it takes some work to make it happen, concentrating on a particular view and trying to see the extended cube as one long diagonal rectangle helps. Notice that your eye shifts views as you look around the rectangle. I think the same thing happens in the Boucher – I think artists understood this and used it to create discrete spaces – unified by the connecting geometry which gives the discrete spaces a sense of one space. Margaret Livingstone points out in her book “Vision and Art” that the eye can focus on only a very small area at a time about the size of a quarter. This means that while looking at a painting you experience it from moment to moment and piece by piece.

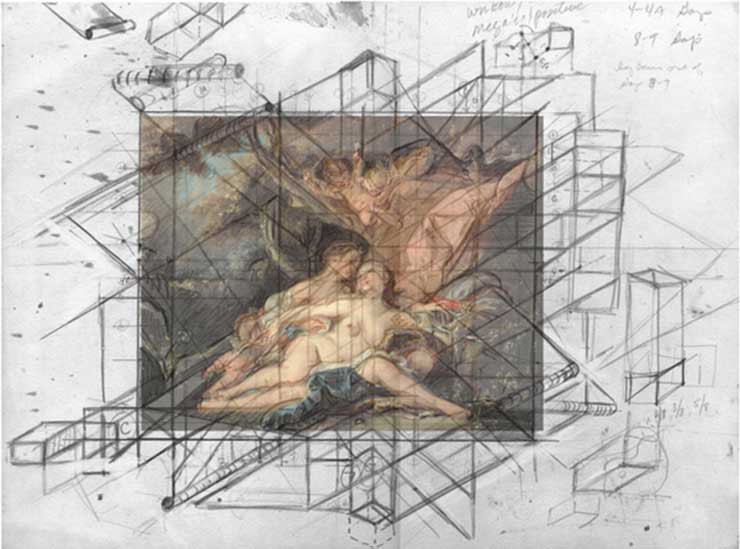

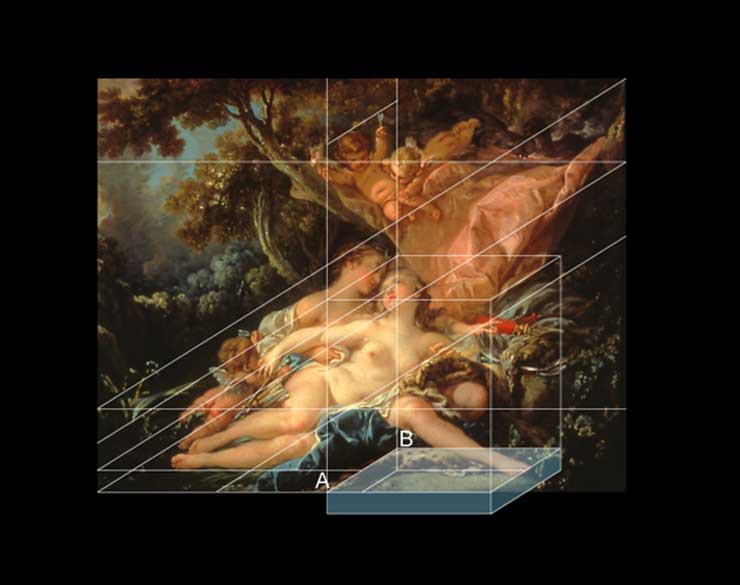

This is the drawing transparently laid over the painting. While there are inaccuracies in my drawing, I think you can still start to see how the foreground shifts between two readings. One as a ground plane that we are looking down on, the small rock augments that view. And the second as a plane shifting up and in front of the picture plane, the spotted drapery helping us along. The next two drawings should clarify the two views.(-> #6)

This overlay of the painting shows our Necker cube in View B or the blue-is-in-front view. We are looking down onto the top as well as the bottom planes of the cube, creating the foreground in the painting, The area in light blue follows a plane that goes back in space from the front edge of the picture A to the edge of the spotted drapery B. The front figure leans back into the space and one feels she looks up into the face of the figure behind.

This overlay of the painting shows our Necker cube in View A or the red-is-in-front view. We are looking up at the bottom of the cube and the foreground in the painting now shifts so the point B is closer to you than point A.The area in light blue follows a plane that comes out in space in front of the picture plane (the rectangle that defines the picture). The front figure now leans forward into the space and one feels she is no longer looking up at the other figure but in front and into a more forward space.

And this is why the right arm of the front figure was so difficult to judge – it depended on how I was reading it!

Leave a Reply